How leaving out explanations kicked historical linguistics upward

Previously on Shells and Pebbles

How many people could read Arabic script in

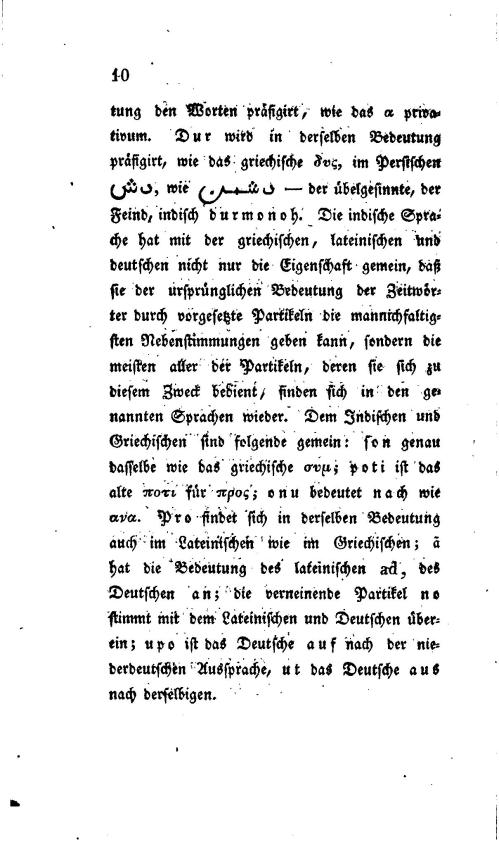

Germany around 1800? The question struck me in 2006 as I was making my

first steps in intellectual history with a paper on Friedrich Schlegel’s

Über Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (1808). Schlegel’s

book – now considered a groundbreaking work in comparative linguistics –

includes samples of untranscribed Persian, to show that Persian is part

of the same language family as Sanskrit, Greek, Latin and German and

has the same “organic” system of conjugation. You don’t really need to

know Arabic script to get that point, and for all we know Schlegel had

at best a very limited grasp of Persian. But if you want to test and

elaborate Schlegel’s ideas, well yes, then you need to. The use of Arabic

script in a book for German readers is unmistakably snobbery, but the

real question is whether that snobbery was also useful.

Seven years later I still don’t know the answer to my initial

question, but I can make an educated guess. There was Arab printing

type. Professor Michaelis in Göttingen (actually Schlegel’s

uncle-in-law) was teaching Arab to generations of theology students. The

Austrian mission to the Sublime Porte included a school for translators

– the so-called Sprachknaben – among whose pupils was Joseph von

Hammer-Purgstall. (At that point Turkish was still written in Arabic.)

Knowledge of oriental languages was an asset, if far from mandatory for

theologians, and many learned pastors dallied in Hebrew and Aramaic.

Wilhelm von Humboldt knew the basics of 33 languages; Adelung and Vater

made a compilation of Paternosters in all the 500 known languages; a

decade later, Goethe wrote West-Östlicher Divan. Still, there

could have been hardly more than a thousand people capable of reading

Schlegel’s Persian at the time, and these need not have been Schlegel’s

readers.

Schlegel is far from unique in that kind of snobbery. Jakob Grimm’s Deutsche Grammatik and the Deutsches Wörterbuch require substantial work and training to even make sense to the reader – for

me, several courses in German historical linguistics under the eminent

Dr. Quak were not enough. The important thing is, Grimm’s contemporaries

were in the same fix. The work of the Grimm brothers does not “reflect”

the state of learning in the early 19th century. Rather, they were intentionally upping the standards so as to require others to keep up and finally turn Germanistik into a hard science. In his reviews, gathered in Kleine Schriften, we can see Jakob Grimm asserting a gatekeeper role: the editorial work of others (most others,

with the exception of Lachmann) is rejected in downright brutal terms

as “sloppy”, “useless”, and “outdated”. E.F.K. Koerner and Joep Leerssen

have it that Grimm only became so severe after his own first work, the Altdeutsche Wälder, had met with a similar crushing review from August Wilhelm Schlegel, the less original but hard-working Schlegel brother.

We could call this phenomenon the performative use of snobbery. (“Performative”

is a term of art from speech act theory; it means to bring something

about by saying something, or more widely by performing some symbolic

act.) Just as composers like Liszt, Rachmaninov and Ligeti have been

upping the standards for pianists by writing “unplayable” scores,

scholars have been kicking the discipline upward not merely by writing

programmatic texts but also by leaving out “unnecessary” information.

The learned and wealthy public of Europe could gloat over the

magnificent prints from the Description de l’Egypte, but the Monumenta Germaniae Historica are

absolutely useless and unappealing to the lay reader. (By contrast, one

of Grimm’s reviews takes the British parliamentary archives to task for

publishing all their medieval charters in prestigious folios without

any consideration of scholarly relevance, “made to gather dust”.) In

doing so, the Grimms and Schlegels and others have introduced a new

“paradigm” in the original sense of the term: an example for others to

emulate. That “paradigm” does not per se include a Gestalt switch of

different world views, but it does include a new way of ordering and

presenting findings, of transforming information into knowledge. To get

that founded, a little snobbery is indispensable.

Performatives can also fail. If people do not acknowledge your act or

follow suit, then the attempt is (Austin’s term) “infelicitous”. For

instance, the Grimms and Lachmann also felt that Fraktur was a barbaric

alphabet and that capitals were a pedantic rudiment. So they published

their works in Latin letters, without capitals. Unfortunately for them,

the rest of Germany went on printing in Fraktur until Hitler finally

abolished it. In spite of the Grimms, German nouns still start with

caps.

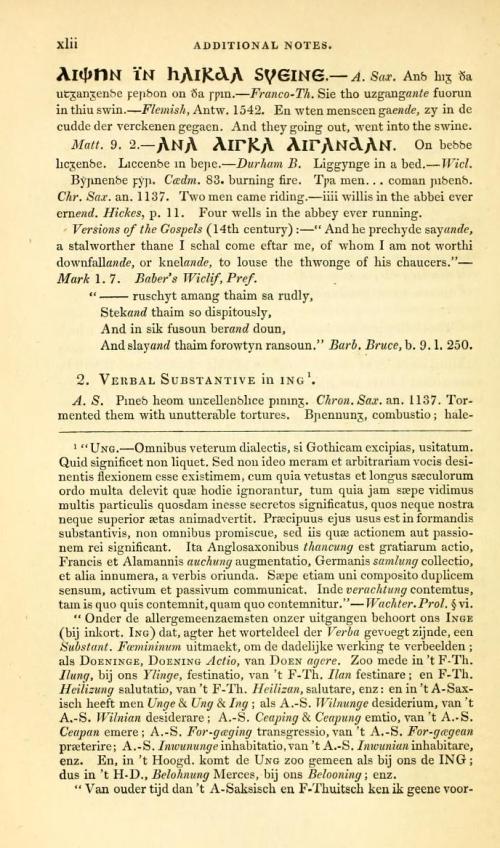

Even works that are widely acknowledged as groundbreaking can still fail to break ground. John Horne Tooke’s Epea Pteroenta; or The Diversions of Purley (2 vols, 1785-96) was like Schlegel’s Über Sprache und Weisheit in

many respects. It was an idiosyncratic, slightly bizarre work which

presented a sensible idea supported by some samples in an opaque script

and a spurious overall argument. In Horne Tooke’s case, the sensible

idea was that language is not entirely representational; only nouns and

verbs stand for things and events, and all other words are

“abbreviations” that etymologically derive from these two. To make this

case, Horne Tooke presents a set of etymologies bad enough to be called

Heideggerian, and supports them with samples of Anglo-Saxon and Old

Gothic. Now Anglo-Saxon is relatively easy to grasp. Old Gothic is not.

Its script is an artificial alphabet modeled on Greek, created in the 4th

century AD by bishop Ulfila to translate the bible to the Ostrogoths.

The language and the whole branch of Germanic to which it belonged are

now extinct. The main source we have for it is the 6th-century Codex Argenteus, now

in Uppsala. Apart from the few dozen members of the Royal Society of

Antiquaries, few people could be expected to be able to read that.

Horne Tooke’s initial success was greater than Schlegel’s. For a few decades, The Diversions of Purley was

generally regarded as the best work in the study of language in

England, only to be superseded by William Jones’ posthumous fame when

the work of the Asiatick Society had sparked off a real revolution

among German scholars. The problem was not that Horne Tooke’s

etymologies were spurious; so was Schlegel’s idea of “organic”

declination as a sign of “divine revelation” as the source of

Indo-Germanic languages. But Schlegel’s original idea – systematically

comparing roots and declensions – could easily be replicated and

elaborated by more sober scholars, such as Bopp, Rask, Humboldt and his

boring brother August. Horne Tooke may have grasped, in hindsight, the

essentials of a structuralist approach to language, but etymology is not

the way to do that. His work continued to be reprinted well into the

1850s for the delight of the learned; Über Sprache und Weisheit was not, because it was devoured by its offspring.

For a closing note, let’s press the analogy further. How many people could read Old Gothic in late 18th-century

England? Less than a thousand, for sure. Anglo-Saxon still had some use

in the study of charters and local inscriptions; Old Gothic was only of

very remote antiquarian interest. But it had a print record. The text of the Codex Argenteus had been published in Oxford in 1750, with a grammar and Latin translation. There are samples of it in several issues of Archeologia, the journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries; in Thomas Astle’s The Origin and Progress of Writing (1784),

actually a field guide to deciphering medieval manuscripts; and even in

the works of George Hickes a century earlier. In short, if you wanted,

you could find out. The use of Old Gothic type in such works was not

meant to make them completely arcane, but to make them more interesting

for those willing to make an effort. It was that level of scholarship

which Horne Tooke hoped to align with in putting his etymologies in

untranscribed Old Gothic. And that, indeed, is snobbery.

There is a moral to this. When old books seem hard to understand, it

need not be because the past is a foreign country, or because we lack a

shared set of assumptions. It can also be because they were meant to be

difficult.

maandag 15 juli 2013

Abonneren op:

Reacties posten (Atom)

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten